Civil War soldiers loved to receive letters from home. Wives, mothers, and sweethearts also sent care packages to their soldiers. Even if a pie didn’t survive postal delivery intact, men still devoured every edible crumb with a thankful heart.

Soldiers purchased envelopes to send their replies back home. One of the fun traditions of the time was that these envelopes were decorated by those who manufactured them.

Flags, patriotic scenes, portraits of Union generals, and army camp scenes were printed on the envelopes, or “covers” as they were also called.

John D. Billings, Union soldier and author of Hardtack and Coffee, wrote of a young man who collected over 7,000 decorated envelopes from the war—each with a unique design.

Some featured specific regiments, listing battles where they fought.

Billings kept a few envelopes from his days in the war. One contained a 34-star border, a star for every state in the Union at the time. An eagle held a shield and a streamer which read, “Love one another.”

Another from his collection showed a drawing of the earth with “United States” printed on it and an American eagle above it. The inscription was “What God has joined, let no man put asunder.”

A third was a sketch of a man with moneybags riding horseback at breakneck speed. The inscription: “Floyd off for the South. All the Seceding States ask is to be let alone.”

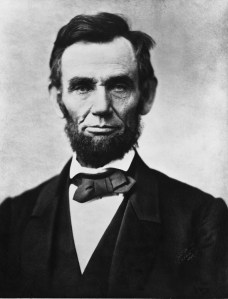

One showed President Washington’s portrait with the inscription of “A Southern Man with Union Principles.”

Billings wrote that the designs expressed the feelings of Northerners.

Billings wrote that the designs expressed the feelings of Northerners.

Union soldiers received envelopes from the U.S. Christian Commission with their organization’s stamp and the words “Soldier’s Letter.”

The Postmaster General allowed soldiers to send letters without stamps, representing prepayment, beginning in 1864. They had to write “Soldier’s Letter” on the envelope.

One soldier wrote the following verse for the Postmaster General:

“Soldier’s letter, nary red,

Hardtack and no soft bread,

Postmaster, please put it through,

I’ve nary cent, but six months due.”

-Sandra Merville Hart

Sources

“American Civil War Soldier Letters Home,” Americancivilwar.com, 2017/02/08 http://americancivilwar.com/kids_zone/soldiers_letters_civil_war.html.

Billings, John D. Hardtack & Coffee, University of Nebraska Press, 1993.