by Sandra Merville Hart

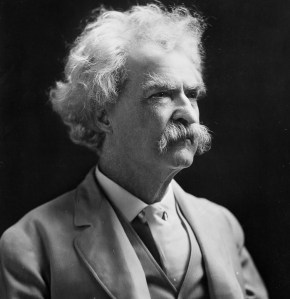

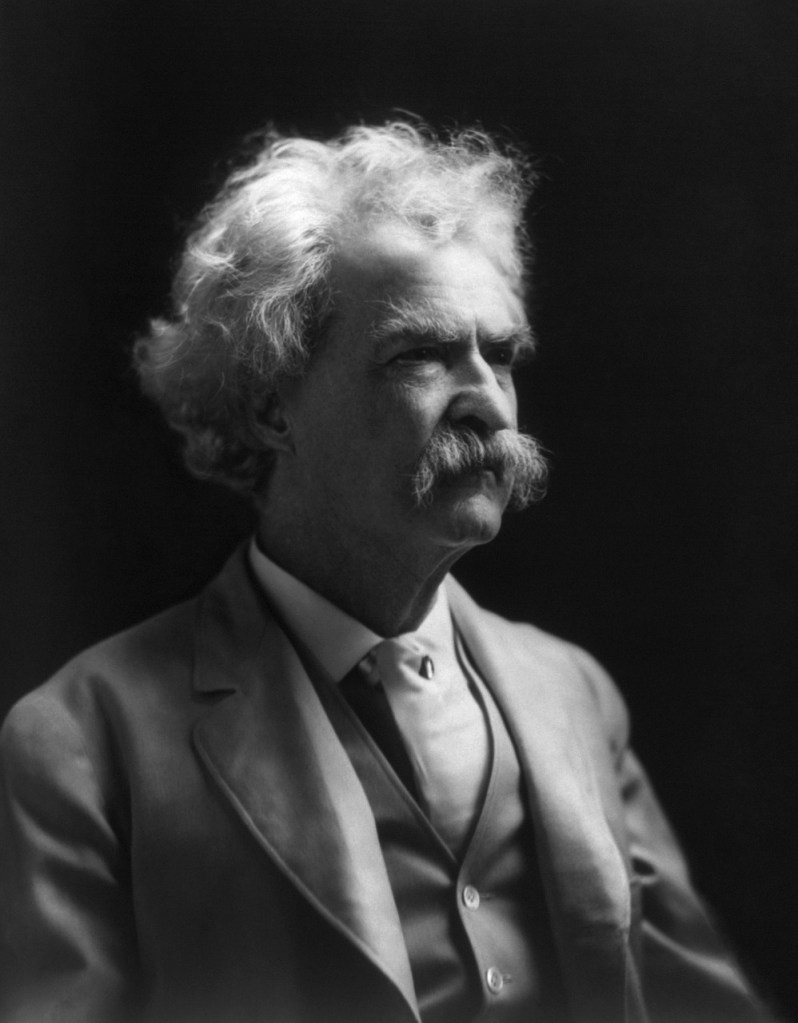

Mark Twain’s life was at a pivotal moment in the 1860s.

He was out of the States and in Nevada Territory where fortunes were made and lost mining for silver. He ought to know. His part-ownership in a silver mine had made him a millionaire. Through the worst of misfortunes, Twain lost his interest in the mine in ten days.

What was next for him? He had held a variety of positions: grocery clerk, blacksmithing, bookseller’s clerk, drug store clerk, St. Louis and New Orleans pilot, a printer, private secretary, and silver miner. He felt that he had mastered none of these professions. What does one do after losing a million dollars?

He gave in to misery. He had written letters to Virginia’s Daily Territorial Enterprise, the territory’s main newspaper in earlier days; it always surprised him when the letters were published. It made him question the editors’ judgment. His high opinion of them ebbed because they couldn’t find something better than his literature to print.

As Twain wondered what his future held, a letter came from that same newspaper offering Twain a job as city editor. Though he had so recently been a millionaire, the twenty-five-dollar salary seemed like a fortune. The offer thrilled him.

Then doubts set in. What did he know of editing? He felt unfit for the position. Yet refusing the job meant that he’d soon have to rely on the kindness of others for a meal, and that he had never done.

Necessity forced Twain to accept an editor’s job for which he felt ill-equipped. He arrived in Virginia, Nevada Territory, dressed more as a miner than an editor in a blue woolen shirt, pantaloons stuffed into the top of his boots, slouch hat, and a “universal navy revolver slung to his belt.”

The chief editor, Mr. Goodman, took Twain under his wing and trained him to be a reporter. It wasn’t long before the young man discovered he’d stumbled upon a profession in which he excelled.

What would have happened if Mark Twain hadn’t lost a million dollars? His words may have been lost to us. Such classics as The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and The Prince and the Pauper might never have been written.

When we ponder our failures, our rejected works, and lost opportunities, we should remember that situations change. We won’t always feel as we do today. God has the ability to put us in the right place at the right time with the right attitude.

Just like He did with Samuel Clemens, America’s beloved Mark Twain.

Sources

Twain, Mark. Roughing It, Penguin Books, 1981.