National Cemetery, Gettysburg

Rain and clouds that mark the Pennsylvania skies on the early morning of November 19, 1863, soon clear to give an exhilarating nip in the air in and around Gettysburg. After a lively evening in the crowded streets last night, folks are still entering town for the important occasion of dedicating the new national cemetery.

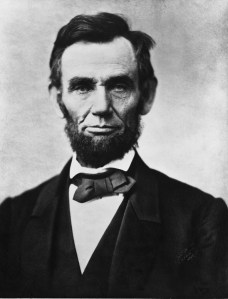

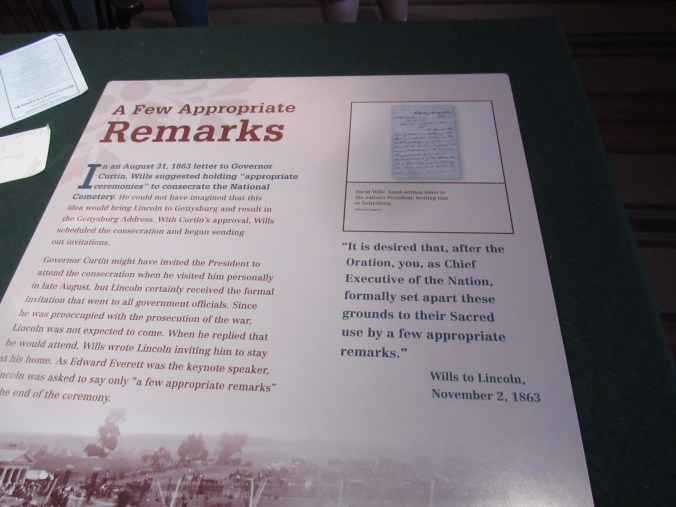

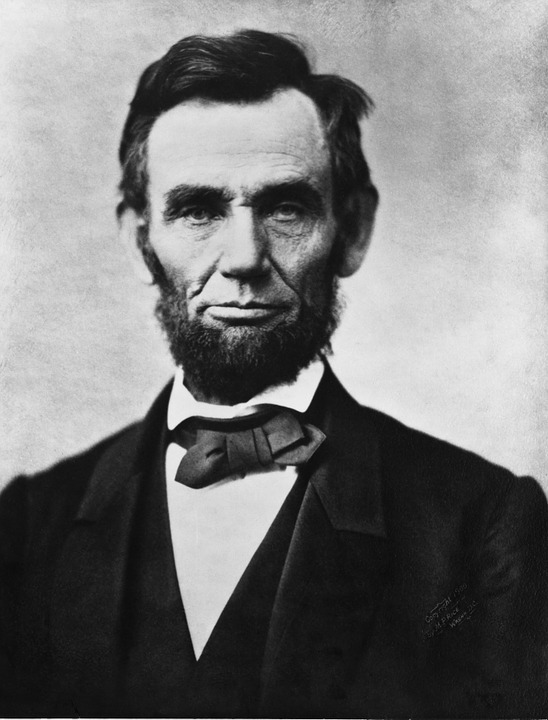

President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William H. Seward take a carriage ride to the Lutheran Seminary grounds where fierce fighting took place on July 1, 1863, the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg.

They return in time to change for the dedication ceremony. Before 10 am, Lincoln emerges from David Wills’ home where he spent the night. He is dressed in black, wears a black frock coat, and carries white gauntlets. Sad. Serious. A wide mourning band adorns his stovepipe hat in memory of his son, Willie, who died of typhoid fever on February 20, 1862.

People press around him, shaking his hand even after he mounts his horse. They cheer for him. The marshals motion the crowd back.

The Marine Band begins the procession followed by a squadron of cavalry, two artillery batteries, and an infantry regiment. President Lincoln rides with several generals, nine governors, Cabinet members, and three foreign ministers among others.

Edward Everett, the main speaker, tours the battlefield and does not participate in the procession.

A 12’ x 20’ platform has been built for the occasion. Honored guests take their place on the three rows of ten chairs each. There are other chairs scattered on the platform and chairs at a table in back for reporters.

A tent stands at the east end of the platform—at Everett’s request and for his use. He emerges from this tent. David Wills, organizer of the event, and New York Governor Seymour escort him to his seat beside Lincoln in the middle of the front row.

Bright sun shines down on the spectators arranged in a semi-circle by the marshals. Many, like Lincoln, wear mourning.

Bright sun shines down on the spectators arranged in a semi-circle by the marshals. Many, like Lincoln, wear mourning.

The pleasing array of flags, banners, and costumes of those in attendance do not mask the signs of the recent battle, where the fields are still littered with broken muskets, canteens, and bits of gray or blue uniforms.

The Marshal-in-Chief Ward H. Lamon is not on the platform to begin the ceremony so his assistant, Benjamin B. French, signals the Birgfield’s Band. They play “Homage d’un Heroes,” a funeral dirge.

Lamon nods to Rev. Thomas H. Stockton to pray. The emotional prayer of the chaplain of the House of Representatives brings tears to many eyes, including Everett and Lincoln.

Next, Lamon calls on the Marine Band. They play Martin Luther’s hymn “Old Hundred.”

Lamon then introduces Edward Everett as the speaker of the day.

Everett speaks for about two hours. The President listens with kind, thoughtful attention. Lincoln rises and shakes Everett hand while some in the crowd applaud at the end.

The Maryland Musical Association sings “Consecration Hymn” that was written by Benjamin B. French for the dedication.

Lamon introduces the President of the United States.

National Cemetery, Gettysburg

Lincoln steps forward. He extracts a paper from his pocket. He puts on his spectacles. The crowd is silent as they look up him.

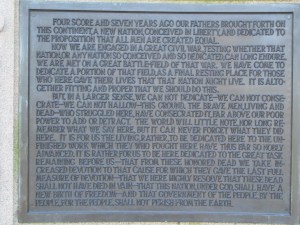

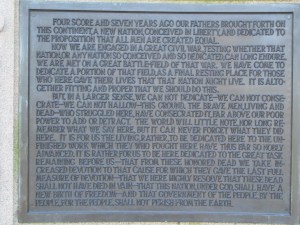

The President gazes at the solemn mourners … at soldiers who will never forget the battle or their comrades. “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

“Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

Gettysburg Address at the Soldiers National Cemetery

“But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

The crowd gives President Lincoln three cheers and then another three cheers for the Governors.

Birgfield’s Band accompanies a chorus of Gettysburg men and women.

Lamon nods to Rev. Henry L. Baugher, who leads those gathered to close the ceremony with a benediction.

Lincoln participates in the procession that leads back to David Wills’ home, where he eats dinner and then receives guests. He attends a service at the Presbyterian Church and then boards a train. It is time to return to Washington D.C.

Back at the cemetery, some mourners remain until darkness falls.

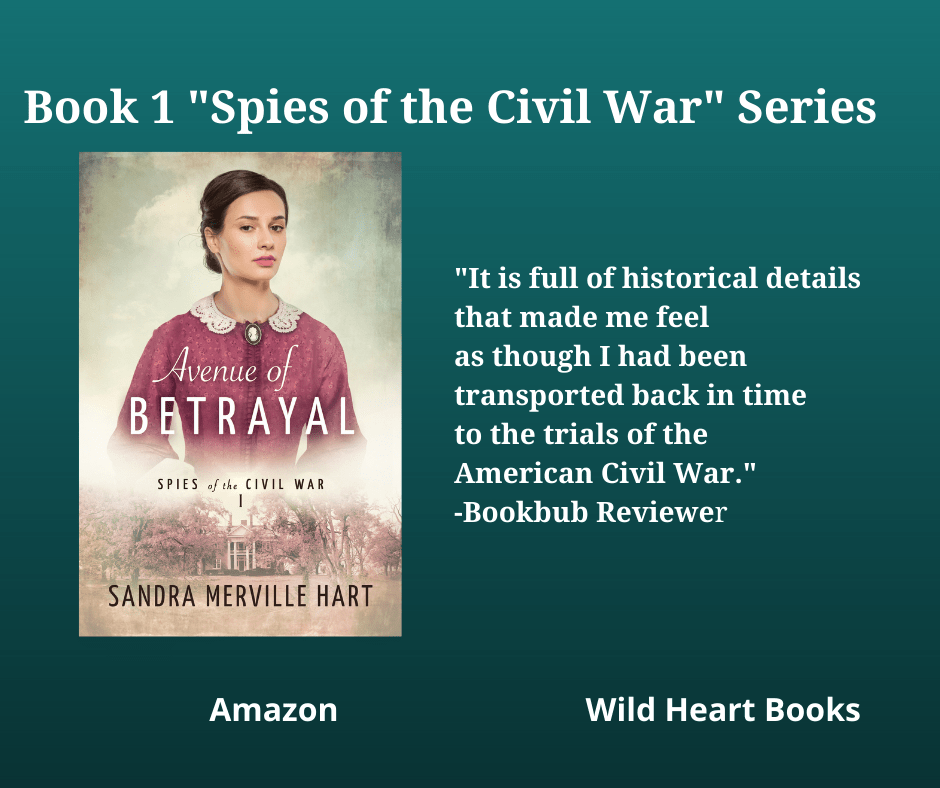

-Sandra Merville Hart

Sources

Sources

Carmichael, Orton H. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, The Abingdon Press, 1917.

Gramm, Kent. November: Lincoln’s Elegy at Gettysburg, Indiana University Press, 2001.

Klement, Frank L. The Gettysburg Soldiers’ Cemetery and Lincoln’s Address, White Main Publishing Company, Inc., 1993.