by Sandra Merville Hart

Asa Whitney, a New York merchant, planted the idea of a transcontinental railroad when he petitioned Congress for federal funding of a sixty-mile strip in 1845, but it wasn’t until Theodore D. Judah caught the vision that things began to happen. Judah believed the Donner Pass was the perfect area for the railroad to pass through the Sierra Nevada mountains, and, as the engineer of the Sacramento Valley Railroad, he wanted to build it.

He brought Leland Stanford, Charles Crocker, Collis P. Huntington, and Mark Hopkins in on the project, leading to the establishment of Central Pacific Railroad Company of California.

Congress passed the first Pacific Railway Act on July 1, 1862. It stated the Union Pacific was to start in Omaha, Nebraska, and build toward the west. The Central Pacific started in Sacramento, California, and built toward the east to meet them roughly halfway.

The second Pacific Railway Act (July 2, 1864) doubled the land grants to 12,800 acres for every mile of track built. They also received $48,000 in government bonds for each mile. This increased the competition between the two companies.

The Civil War hampered Union Pacific’s efforts to build. Though they began in December of 1863, little was accomplished for the remaining two years of the war.

The western team began about a month before. Sadly, the man who had laid so much groundwork for the project didn’t see it to completion. Judah died of yellow fever in November of 1863, shortly after Central Pacific pounded the first spikes.

The Sierra Nevada mountains slowed Central Pacific’s progress. They hired Chinese workers for this grueling task. Nine tunnels were blasted the mountains in order for the track to be laid.

Once the war ended, the Union Pacific made progress westward across the prairie. Civil War veterans and Irish immigrants had to cope with attacks from Native Americans. Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapahoe were among the attacking tribes.

Union Pacific workers had their own difficulties to contend with—the Rockies. Even with these obstacles, the group from the east was in Wyoming in the summer of 1867, and had laid almost four times the miles of track as the western team.

Once Central Pacific made it to the other side of the Sierra Mountains in June, they made significant progress.

The competition was on now. Unfortunately, the workmanship suffered and some the sections were later rebuilt.

In March of 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant told the two companies to agree on a meeting point. They chose Promontory, Utah. A symbolic gold spike was driven in a special “Golden Spike Ceremony” on May 10, 1869. It linked both railroads, marking the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad.

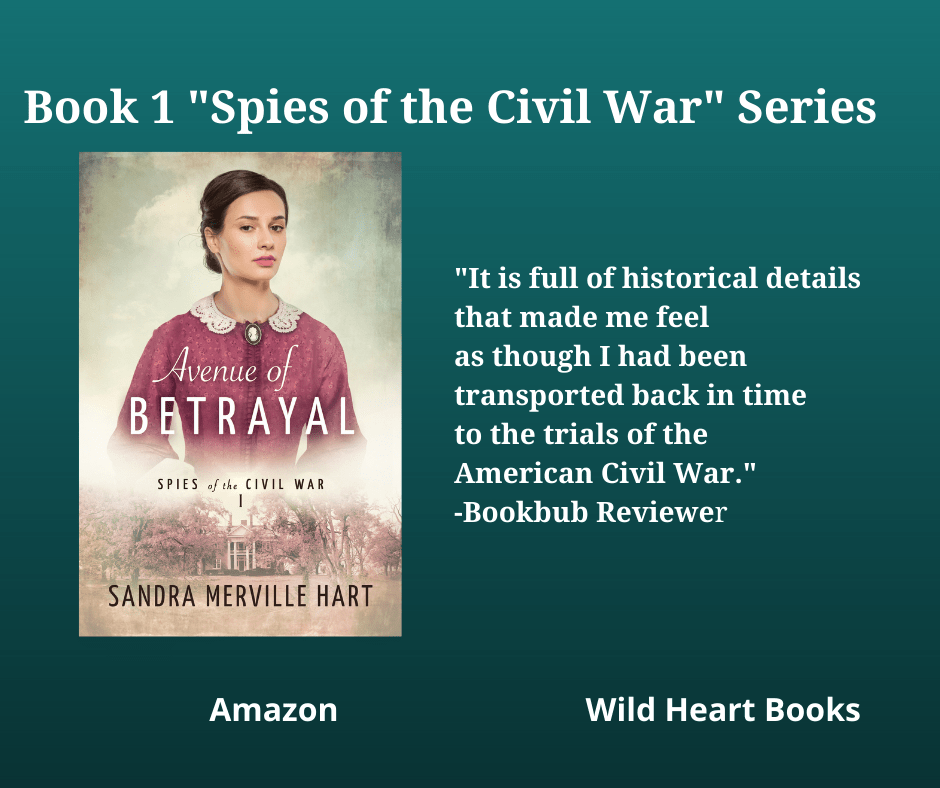

The hero in my novel, Avenue of Betrayal, Book 1 of my “Spies of the Civil War” series, dreams of participating in building the Transcontinental Railroad. The fictional Union officer hopes that the war doesn’t last so long that he misses his opportunity. As you read in this article, Civil War veterans were used to build the railroad after the war ended. I was thrilled to use such an important part of our history in the story.

Sources

“Central Pacific Railroad,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2022/02/22 https://www.britannica.com/topic/Central-Pacific-Railroad.

History.com Editors. “Transcontinental Railroad,” History.com, 2022/02/22 https://www.history.com/topics/inventions/transcontinental-railroad.

“Pacific Railway Acts,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2022/02/22 https://www.britannica.com/event/Pacific-Railway-Acts.

“The Transcontinental Railroad,” Library of Congress, 2022/02/26 https://www.loc.gov/collections/railroad-maps-1828-to-1900/articles-and-essays/history-of-railroads-and-maps/the-transcontinental-railroad/.

“Transcontinental Railroad,” History.net, 2020/06/19 https://www.historynet.com/transcontinental-railroad.

“Union Pacific Railroad Company, Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2022/02/22 https://www.britannica.com/topic/Central-Pacific-Railroad.