by Sandra Merville Hart

City Hotel, located at 1401 Pennsylvania NW in Washington DC, was expanded after Henry Willard leased it in 1847. He soon brought his brother, Joseph, into to the business and changed the name to Willard Hotel. They built a six-floor hotel on the southwest corner of 14th and F Streets. The brothers purchased a Presbyterian Church on F Street and converted it to a meeting hall with an auditorium called Willard Hall.

Henry went the extra mile to make his hotel successful. He greeted hotel guests as they stepped out of the stage. He was at the Central Market before dawn to select the highest quality of products available to serve for in his hotel’s dining rooms. Henry donned a white apron to carve meats at the dining table.

By the Civil War, the hotel was a center of activity for the bustling capital then known as Washington City. Luxurious gentlemen’s and ladies’ dining rooms could accommodate 2,500 diners daily. Elegant parlors invited guests to linger after a meal before retiring to their rooms.

The hotel also boasted of a 150-foot ballroom, where it hosted lavish events like the Napier Ball, given as a farewell on February 17, 1859, to the British Ambassador Lord Francis Napier and Lady Anne Napier. Eighteen hundred guests paid an expensive price of $10 each to attend. The ball’s success boosted the hotel’s prestige.

Willard’s boasted another honor—both Franklin Pierce and Abraham Lincoln stayed at their hotel before their presidential inaugurations.

After the war began, Union regiments poured into the city for further training and the hotel lobby became a common meeting place for Union officers to make their reports.

One of these regiments, the 11th New York Infantry, was made up of firemen under Colonel Elmer F. Ellsworth. The entire regiment wore red shirts, gray breeches, gray jackets, and red caps, so they stood out in a crowd.

On May 9, 1861, the Willard brothers had cause to be grateful for Ellsworth’s Zouves when fire engulfed Samuel Owen’s tailor shop, which adjoined their hotel. With equipment borrowed from local firehouses, Ellsworth’s men helped the Washington Fire Department extinguish the blaze. His entire regiment was eventually called to fight the fire and Ellsworth, using the fire chief’s trumpet, took command until the crisis ended.

Henry Willard was so pleased with the results that he invited them all to breakfast. Undoubtedly, the situation would have been much worse without so many capable firefighters.

Union soldiers training for the Civil War battlefields faced a familiar battle that day.

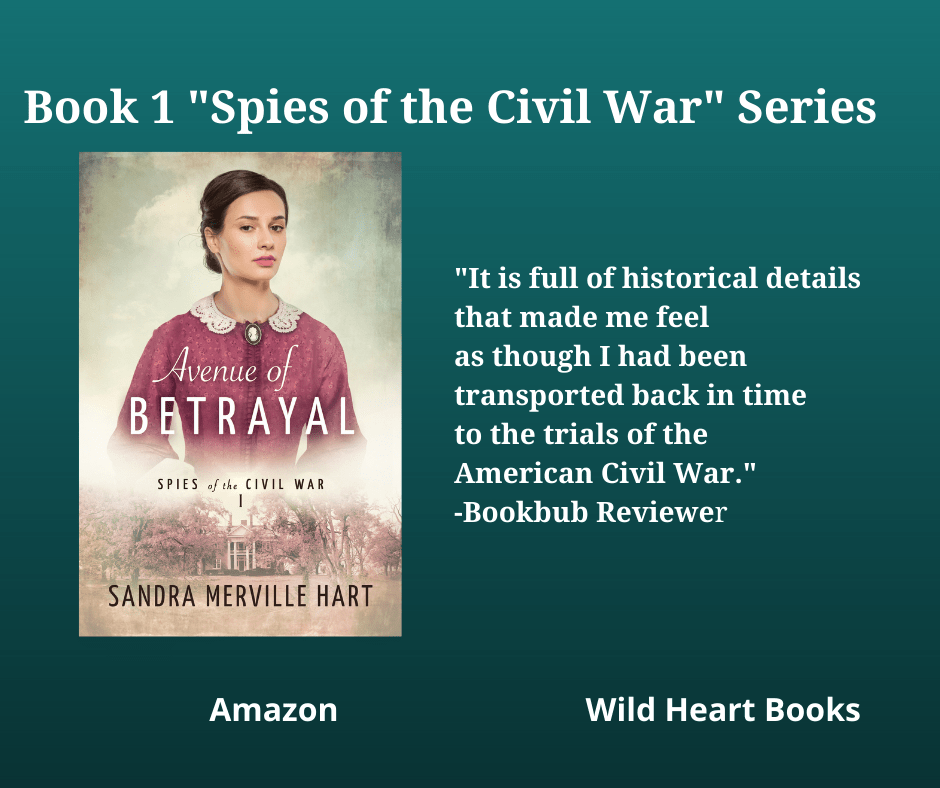

There is a scene at the Willard Hotel when characters in my novel, Avenue of Betrayal, Book 1 of my “Spies of the Civil War” series, dine there. I was thrilled to use such an important location in the story.

Sources

“11th New York Infantry Regiment,” Wikipedia, 2022/02/25 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/11th_New_York_Infantry_Regiment.

“A Ball at Willard’s,” White House Historical Association, 2022/02/25 https://www.whitehousehistory.org/photos/a-ball-at-willards.

Epstein, Daniel Mark. Lincoln and Whitman: Parallel Lives in Civil War Washington, Ballantine Books, 2004.

Selected by Dennett, Tyler. Lincoln and the Civil War In the Diaries and Letters of John Hay, Dodd, Mead & Company, 1939.

“The Willard Hotel,” White House History, 2020/06/11 https://www.whitehousehistory.org/the-willard-hotel.

“The Willard Hotel in the 19th Century,” Streets of Washington, 2020/06/11 http://www.streetsofwashington.com/2012/07/the-willard-hotel-in-19th-century.html.

Waller, Douglas. Lincoln’s Spies, Simon & Schuster, 2019.

“Willard Hotel,” National Park Service, 2020/06/11 https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/wash/dc36.htm.

“Willard InterContinental Washington,” Wikipedia, 2020/06/11 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willard_InterContinental_Washington.