Today’s post was written by fellow author, Linda Shenton Matchett. Welcome to Historical Nibbles, Linda!

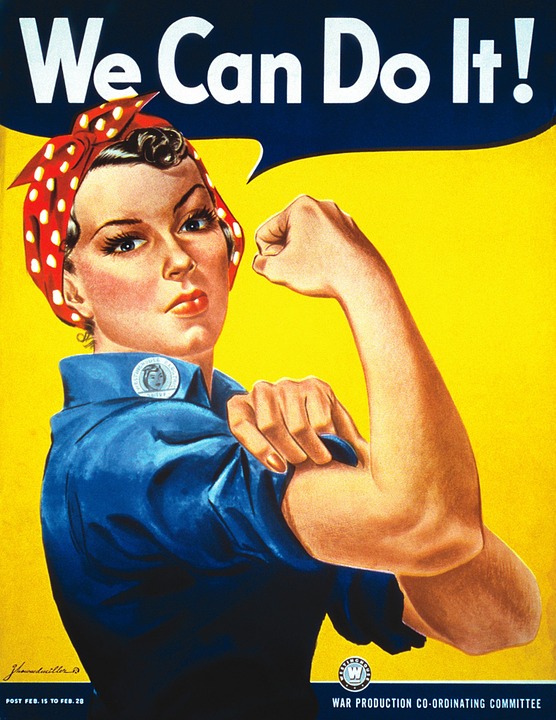

When I was growing up, my folks didn’t believe in “girl jobs” and “boy jobs.” Hence, my brothers learned how to cook, wash dishes, and do laundry, and my sister and I learned how to mow the yard and shovel the driveway among other chores. That philosophy is decidedly different from the cultural norms prior to WWII.

Then war came, and men began to leave the workforce in droves. Support for women to seek volunteer and employment opportunities began at the highest level. In one of his fireside chats, President Roosevelt said, “There need no longer be any debate as to the place of women in the business life of this nation. The enlarging war effort calls for the services of every qualified and able-bodied person, man or woman.”

Unfortunately, for the first eighteen months of the war, organizations and employers struggled to go against deep-seated traditions and concepts making them reluctant to hire women. As a result, there were “boy jobs” and “girl jobs.” One of the organizations where a young lady could work or volunteer without recrimination was the United Service Organization (USO). Founded in 1941 by combining the Salvation Army, YMCA, YWCA, National Catholic Community Services, National Travelers Aid Association, and the National Jewish Welfare Board, the USO had over 3,000 clubs worldwide at its height (there are only 160 day).

Despite ties to the military, the USO is not part of the government, but rather a private nonprofit organization. Therefore, fundraising was necessary to finance its operation. Thomas Dewey (FDR’s opponent in the 1944 election) and Prescott Bush (Grandfather of former President George W. Bush) spearheaded the campaign, and more than thirty-three million dollars was raised. Activities were countless: from billiards and boxing to dancing and darts. Services ranged from sewing on insignias to writing letters on behalf of the men. Candy, gum, newspapers, and other items were available for purchase.

Strict rules ensured the clubs were safe places for the junior hostesses-unmarried women typically in their mid-twenties. Senior hostesses acted as chaperones, and the younger hostesses couldn’t dance with the same man more than twice. Soldiers, sailors, and airmen could smoke at the club, but no was liquor served. In addition, formal attire was required of the girls, and the wearing of slacks was forbidden.

For more information about this worthwhile organization, visit http://www.uso.org.

-Linda Shenton Matchett

May 1942: Geneva Alexander flees Philadelphia and joins the USO to escape the engagement her parents have arranged for her, only to wind up as the number one suspect in her betrothed’s murder investigation. Diagnosed with Retinitis Pigmentosa, she must find the real killer before she loses her sight…or is convicted for a crime she didn’t commit.

Set in the early days of America’s entry into WWII and featuring cameo appearances from Hollywood stars, Murder of Convenience is a tribute to the individuals who served on the home front, especially those who did so in spite of personal difficulties, reminding us that service always comes as a result of sacrifice. Betrayal, blackmail, and a barrage of unanswered questions… Murder of Convenience is the first in the exciting new “Women of Courage” series.

Linda Shenton Matchett is an author, speaker, and history geek. Born in Baltimore, Maryland a stone’s throw from Fort McHenry, Linda has lived in historical places most of her life. A member of ACFW, RWA, and Sisters in Crime, she is also a volunteer docent at the Wright Museum of WWII and a Trustee for the Wolfeboro Public Library. Connect with Linda on her blog.

Sign up for her newsletter newsletter and receive a free short story, Love’s Bloom!